Content

Between two world wars: the Reichspatentamt from 1931 to 1940

Fluctuation due to the economic situation

Consequences of the war and austerity led to the reduction of staff at the Patent Office of the German Reich (Reichspatentamt) to only 752. At the end of 1930, the number of unprocessed applications amounted to 128,000. Economic upswing and downswing also had an impact on the filing figures. In 1930, the number of patent applications reached its peak since establishment of the patent office (78,400), with 79,175 concluded procedures; three years later, the number of patent applications decreased to 55,992 and, in 1940, to 43,479, with 40,504 concluded procedures.

There was an urgent need for more staff. By 1932, about 180 university graduates were hired in a short time frame and experienced staff members were appointed assistant members.

In 1933, the government ultimately involved industry into rearmament. Manufacturers simply had no longer time for their patent applications. It had become impossible to reply to office actions in due time; the pressure to supply munitions in time was too big. The number of pending applications increased and, although fewer new applications were received, reducing the backlog was not possible. It also did not help that additional staff was newly hired for clerical services as well as 100 university graduates as examiners. The staff grew to 1,900 by 1939 - the highest number until then.

The office comprised

- 18 patent divisions,

- 3 trade mark divisions,

- the section for international trade marks,

- the utility model division,

- 2 patent administration divisions,

- 9 units for administrative and legal matters,

- the library,

- the cash office as well as

- 3 registries and

- a photocopying service.

The library was known as the largest technical library in Germany then.

Even though the building in Gitschiner Straße was built in grand style in 1905, it became too small already by the end of the 1920s. Another building with 96 rooms and a second public library was built in 1930 and connected to the main building. Seven years later, the library, which had more than 30 staff members, complained about shortage of space. Another extension provided storage room for the library. In 1939, the 850 rooms were no longer enough. The trade mark divisions' fate of 1893 repeated itself. Since they did not depend on the comprehensive search collection, they moved to the neighbouring rented buildings.

Organisational reforms

Patent application divisions were reorganised and received technically qualified chairs. In order to relieve the technically qualified staff members of administrative tasks, a special patent administration division was established. An advantage was also that this ensured harmonised execution of official tasks. The appeal area received new members and was divided into boards with specific technological fields. Finally, the procedures took less time and the number of concluded procedures rose.

The Patent Act (Patentgesetz) of 5 May 1936 also led to organisational changes. From then on, it was up to the office to decide on cancellation requests, ordinary courts were no longer competent. Cancellation proceedings were thus handled faster, more cost-efficient and subject to uniform principles. The courts were not able to do so because they had to consult costly expert opinions. Each technological field decided in a panel of one legal and three technical specialists; the utility model division processed more than 300 cancellation requests each year.

Legal reforms

The reform, intended to be implemented before World War I, again fell through in 1930. This was not due to differences of opinions but only due to the fact that the committee on legal affairs only dealt with foreign affairs and criminal matters. Hope for a legal reform was ultimately abandoned on 18 July 1930 when President of the Reich Paul von Hindenburg dissolved the parliament. The last resort was an emergency decree implementing some urgent amendments. For example, there were demands to extend the patent term by counting from a later date or to integrate the whole draft into the emergency economic programme. However, there were also divergent opinions, such as that of the then President of the Reichspatentamt Johannes Eylau (1928-1933) in December 1931. The Ministry of Justice of the German Reich felt no need for hurry and introduced the bill in the German parliament only on 26 April 1932, shortly before the second dissolution of the German parliament through Paul von Hindenburg on 4 June 1932. The Ministry of Justice then decided to at least reduce the fees of the patent office in view of the economic crisis. The Nazi government, which came to power in 1933, implemented the legal reform within three years. It provided then the basis for the possibility to grant financial relief in official and court proceedings to impecunious inventors.

The acts on industrial property protection of 5 May 1936 provided for the protection of only the inventor's intellectual property. According to the official explanatory memorandum, the creativity present in the German people was invaluable. Therefore, it is described as one of the noblest duties to promote creativeness and to protect resulting works against unfair use. The Reichspatentamt continued to be critical of this decision but bowed to the political will.

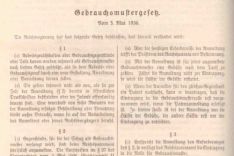

Utility Model Act of 5 May 1936

Before 1936, the standard was absolute novelty, according to which an invention is new if it does not form part of the state of the art or, in other words, if it is new compared to all knowledge publicly known at the date of filing the application. In contrast, the grace period defines relative novelty. Inventors were able to file their invention for application up to six months after it had been used or disclosed to the public. Since the invention had been part of the state of the art at the filing date, the applicant was able to make use of the grace period.

Within the framework of European harmonisation, the grace period for patents was abolished in Germany in 1978, it remained in force for utility models though. As of now, the absolute novelty standard applies to patents.

Management of the patent office in 1933/1934

President Johannes Eylau

(1928-1933)

Following the final state examination, he worked in the judicial service, as a local court judge and as a judge at Regional Court I in Berlin. In World War I, he lost his left eye and was captured by the French as a prisoner of war for three years in 1916. Following diverse activities in the field of law, he was appointed President of the Reichspatentamt in 1928.

When the Nazis hoisted the swastika flag on the patent office building on 30 January 1933, he took it down himself. Subsequently, he was transferred to the Ministry of Labour to a non-management position in mid-1933. Pursuant to Section 5(1) of the Professional Civil Service Restoration Act (Gesetz zur Wiederherstellung des Berufsbeamtentums) of 7 April 1933, each civil servant had to accept being transferred to another position of lower rank, but without a negative effect on the salary, justified by a "need of the Service".

Dr. Carl August Johannes Harting

(1933-1934)

Source: ZEISS archive

Finally, the physicist and optical scientist Dr Carl August Johannes Harting was chosen as acting President from 1933 to 1934. Born on 15 February 1868, he worked in different positions following his degree in Physics and joined the patent office in 1908. In 1918, he received the title of Geheimer Regierungsrat (senior civil servant). In 1949, he was awarded the National Prize of the German Democratic Republic (first class) for science and technology thanks to his great contributions in the field of geometrical optics and for reconstruction of the Zeiss works (VEB Carl Zeiss). In 1950, he became honorary member of the German Academy of Sciences.

President Georg Klauer

(1934-1945)

His application for membership in the Nazi Party was refused because, despite his being a "correct civil servant of impeccable character", his political profile was found to be "colourless". Several civil servants joined the party after being pressured without having the desired political convictions. Subsequent to his degree in Law, Georg Klauer became local court judge in 1909, member of the patent office in 1911, served in the Imperial Motor Boat Corps during World War I and was in the Ministry of Justice from 1921. He stayed there until his appointment as President of the Reichspatentamt in 1934, which was under his direction until its dissolution on 21 April 1945.

Pictures: DPMA (unless otherwise noted)

Last updated: 23 January 2024

Not only protecting innovations

Social Media