Content

150th birthday of Carl Bosch

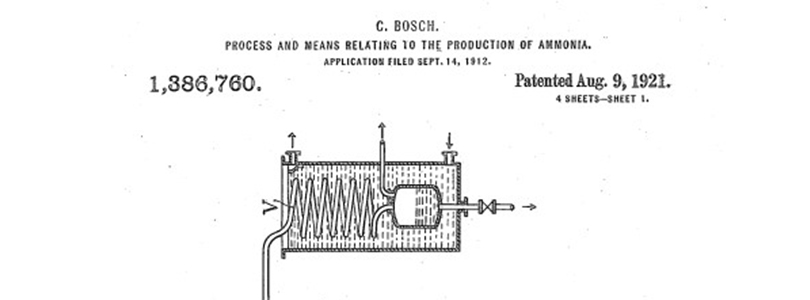

US1386760A

High pressure to feed the world

He was the defining figure of the German chemical industry in the first half of the 20th century: Carl Bosch. His greatest achievement was his contribution to the mass production of fertilizers, to which a large part of the world's population still indirectly owes its food today.

Carl Bosch was born 150 years ago, on August 27, 1874, in Cologne. His father owned a plumbing business. His uncle Robert also worked there for a time, and in 1886 he founded a company under his own name, which is still successful worldwide today and has been the largest applicant for patents at the DPMA for many years.

After an apprenticeship as a locksmith in the Silesian metallurgical industry, Carl Bosch studied mechanical engineering and metallurgy at Charlottenburg Technical University and then chemistry in Leipzig. He completed his studies with a doctorate in organic chemistry ("On the condensation of disodium acetone dicarboxylic acid diethyl ester with bromoacetophenone"). In 1899, Bosch began his professional career as a chemist at the Badische Anilin & Soda-Fabrik (BASF) in Ludwigshafen, where he rose to become Chairman of the Board.

Fritz Haber, professor at the Technical University in Karlsruhe, had carried out essential research into the artificial production of ammonia - the basic component of agricultural fertilizers - and developed a process that he handed over to BASF, which applied for a patent for it ( ![]() DE235421). Carl Bosch's task was to develop a large-scale industrial implementation for this process.

DE235421). Carl Bosch's task was to develop a large-scale industrial implementation for this process.

With high pressure to success

Carl Bosch as Nobel prize laureate

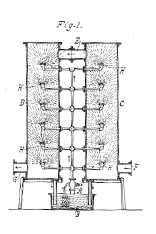

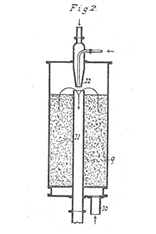

A very difficult task! Among other things, it was necessary to develop suitable reactors that could withstand extremely high pressures and temperatures. Bosch found a way, not least thanks to his metallurgical knowledge, and designed high-pressure reactors in which different types of steel with different pressure and heat resistance were used.

By 1913, he and his team had developed a catalytic high-pressure process for ammonia synthesis, which became known as the "Haber-Bosch process". This was a milestone in the history of chemistry, as the inexpensive production of mineral nitrogen fertilizer from ammonia made it possible to significantly increase agricultural yields. It also gave rise to a completely new industrial branch: high-pressure technology was to have a lasting impact on the chemical industry.

The world's first ammonia synthesis plant was built in Oppau near Ludwigshafen in 1913. After just one year, it was already producing 40 tons of ammonia a day.

Numerous patents

Bosch's work led to a large number of patent, all of which were registered in the name of BASF in Germany, as it was not yet customary at the time to name the author of employee inventions. So Bosch was the author behind, for example, "Process for the production of fertilizers" ( ![]() DE332114), "Process for the production of urea from carbonic acid compounds of ammonia"(

DE332114), "Process for the production of urea from carbonic acid compounds of ammonia"( ![]() DE332679), "Process for the production of ammonium sulphate with the aid of calcium sulphate, ammonia and carbonic acid" (

DE332679), "Process for the production of ammonium sulphate with the aid of calcium sulphate, ammonia and carbonic acid" ( ![]() DE336767)or "Process for the production of nitrogen oxides from ammonia"

DE336767)or "Process for the production of nitrogen oxides from ammonia" ![]() DE366712).

DE366712).

The situation was different in the USA, for example, where numerous patents were registered in Carl Bosch's name, such as „Process of making ammonia“ ( ![]() US957843A), „Production of nitrids“ (

US957843A), „Production of nitrids“ ( ![]() US1027312A), „Purification of hydrogen“ (

US1027312A), „Purification of hydrogen“ ( ![]() US1133087A), „Apparatus for working with hydrogen under pressure“ (

US1133087A), „Apparatus for working with hydrogen under pressure“ ( ![]() US1188530A) or „Process and means relating to the production of ammonia“ (

US1188530A) or „Process and means relating to the production of ammonia“ ( ![]() US1386760A (1,05 MB)).

US1386760A (1,05 MB)).

Chemistry in war

However, ammonia synthesis not only enabled the mass production of fertilizers, but also of explosives. This became crucial with the start of the First World War: the German Reich was no longer able to import the urgently needed saltpetre from Chile due to the war. Bosch, by then director of BASF, made a "saltpetre promise" to the army command: his company would completely replace the saltpetre previously imported by synthetic substitutes. Without BASF's ammonia, the German army would have been defenceless after a short time. BASF produced over 500,000 tons of ammonia for ammunition and grenades every year until the end of the war in 1918.

Fritz Haber also put himself at the service of the German war effort: he became the "father" of warfare with poison gas. The sinister history of chemical weapons began with the first German gas attack on Ypres in 1915, which Haber prepared and coordinated. Poison gas became the first weapon of mass destruction.

Nobel Prize for the fathers of modern fertilization

Nevertheless, Fritz Haber was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for the synthesis of ammonia immediately after the end of the war. A few years later (1931), Carl Bosch also received this prize for his contribution to the Haber-Bosch process. He shared it with Friedrich Bergius "in recognition of their contributions to the invention and development of high-pressure chemical processes". It was the first time in the history of the Nobel Prize that the invention of a technical process was honored.

After the First World War, Bosch took part in the negotiations for the Treaty of Versailles as an economic advisor. He helped to prevent the imminent dismantling of the German nitrate and paint factories. His main argument was the threat of famine if industrial fertilizer could no longer be produced. Haber's Nobel Prize supported his argument, as the Nobel Academy emphasized the global importance that the production of nitrogen fertilizers had gained for food production within just a few years.

Explosion in Oppau

BASF resumed large-scale production of ammonium sulphate nitrate after the war. Although now only fertilizer and no more explosives were to be produced, there was a devastating explosion in 1921 in which almost the entire nitrogen plant in Ludwigshafen-Oppau was destroyed and 559 people died. It was the largest civilian explosion in German history. Bosch had the production of ammonium nitrate in Oppau stopped immediately (it was not resumed until long after his death).

Bosch, who had long been one of the most important corporate leaders in the country, became the figurehead of the German chemical industry in 1925 when he coordinated the merger of the most important companies to form the "Interessensgemeinschaft Farbindustrie" (I.G. Farben AG). This created the world's largest chemical group. Carl Bosch became Chairman of the Board of Management.

Bosch and Hitler

In the 1930s, Bosch moved to the supervisory board and succeeded Max Planck as president of the Kaiser Wilhelm Society (now the MPG). His attitude towards the Nazi regime was ambivalent: on the one hand, he cooperated with and profited from Hitler's economic policies (for example, in the production of synthetic fuel). On the other hand, he stood up for Jewish colleagues and scientists - such as Fritz Haber, who came from a Jewish family. Haber had to flee in 1933 and died shortly afterwards in exile. Despite restrictions, Bosch demonstratively attended a commemoration ceremony organized by Max Planck on the anniversary of Haber's death in January 1935, accompanied by all the directors of I.G. Farben.

Richard Willstätter, one of the many outstanding German scientists with Jewish roots who were expelled by the Nazis, was one of Bosch's friends. He reported that Bosch had told him about a meeting with Hitler, where Bosch had warned that the expulsion of Jewish scientists would set German physics and chemistry back a hundred years. Hitler then shouted: "Then we will work without physics and chemistry for a hundred years!" and ended the conversation.

Carl Bosch lost his positions in industry at the end of the 1930s, probably under political pressure. The inner conflict between his economic and nationalist interests on the one hand and his moral and scientific convictions on the other may have exacerbated Bosch's latent health and mental problems. Depression and alcohol were now taking their toll on him; he attempted suicide in 1939. One year later, on April 26, 1940, he died in his villa in Heidelberg.

Text: Dr. Jan Björn Potthast, Pictures: DEPATISnet, Nobel Foundation / Public domain via Wikimedia Commons, BASF Negativnummer 1795 alt CC by-SA 3.0, Popular Mechanics Magazine 1921 / Public domain via Wikimedia Commons, Scan von Edhace V. Public domain via wWkimedia Commons

Last updated: 16 April 2025

Not only protecting innovations

Social Media